An updated response to Vaush’s ultimate research document, with new sections on statistics, sex reassignment surgery and causes for black crime.

THERE’S A NEW VERSION:

Almost a year ago, a couple of friends and I got commissioned to work on a response to a Google Document (click here) by the Youtuber Vaush. This response was specifically made for his racism in the criminal justice system section. A few days after we made it, we decided to release it to the public incase others wanted to see it, and since then it has gained some steam among Leftists and *some* right wingers. Since then, people in Vaush’s discord have commented on it but have not made a single response to it, but one guy on Reddit did (see his comment here). I commend the guy for actually making a decent response, so I’ll include more in this updated response to respond to what he said. Regardless, it’s been almost a year since I uploaded the original response to my blog, and I have decided to make a more updated response; more studies, better explanations, and a few sections here and there to explain some basic concepts.

I also was not a fan of the original response, especially in respects to the flow of it all as in some sections it got “dirty.” So, all this is basically to fix some stuff I did not like in the original, and include more explanations for the statistically challenged. This is basically a short introduction explaining why I am remaking this, and to inform readers that I’m making some sections to help some of them understand the topic at at hand and the statistics behind it. Regardless, the first section will deal with some basic concepts in statistics, and then the 2nd section will discuss the issue of racism criminal justice — more specifically, a response to the cited studies in the document. Readers familiar with elementary statistics can skip the following section and skip on the response section, but those who need a refresher or a quick guide can continue as normal. Not all that is discussed in the statistics section will show up for every discussion, but it’s important to know some of these stuff as they may nor may not appear from time to time here.

As said above, this updated response is cleaning up things I did not like in the original response, and to flesh out some sections. The biggest update to this is the inclusion of a discussion on statistics, black crime, and the validity of sex reassignment surgery. This is primarily focused on systemic racism, group differences, and transgenders, so some stuff in Vaush’s doc has been left out because it is irrelevant.

Sampling

Sampling in statistics simply means selecting a group in which you’ll collect data from. When doing a study, we want to choose a population first and then get a sample from that population to study. A population is an entire group of people who we want to draw conclusions from, and a sample is a specific group of individuals from that population who we will study. Remember: A population can be defined in terms of geographical location, age, income, and many other characteristics.

Example:

Researchers want to see how watching TV influences teenagers in California. To study the effects of TV consumption, researchers gather a sample of 300 teenagers from California and give them a survey to see how watching TV has influenced them.

Population: Teenagers in California

Sample: 300 teenagers from California

We can’t study everyone in a population, so that’s why we have a sample. When collecting a sample, we want it to be as representative of our population as close as possible. This is why we do random samples. Random samples are people taken from a population at random, sort of like picking names out of hat. When we have random samples, our results will be more accurate because they’re not biased. There’s different types of sampling, some good and some bad, that will be detailed below

Good Samples:

- Simple random sample: Every member and set of members has an equal chance of being included in the sample. Technology, random number generators, or some other sort of chance process is needed to get a simple random sample. Random samples are usually fairly representative since they don’t favor certain members

- Stratified random sample: The population is first split into groups. The overall sample consists of some members from every group. The members from each group are chosen randomly.

- Cluster random sample: The population is first split into groups. The overall sample consists of every member from some of the groups. The groups are selected at random

- Systematic random sample: Members of the population are put in some order. A starting point is selected at random, and every nth member is selected to be in the sample.

When our sample is representative of the population we are trying to measure, it yields results that are more applicable to the population we are trying to study.

Bad Sampling:

- Convenience sample: The researcher chooses a sample that is readily available in some non-random way. (Ex. choosing a sample of people who live in your home since they’re readily available and aren’t random people)

- Voluntary response sample: The researcher puts out a request for members of a population to join the sample, and people decide whether or not to be in the sample. (Ex. A researcher asks gay couples at a bookstore to join his study)

These types of samples are not representative, meaning that they do not reflect the population we are trying to study because they lead to bias. In this context, bias means that certain people are being favored and these people may not be representative of the population. Thus, the results will be biased, and our findings are only applicable to our sample and not the population we want to study.

When doing a study, we want our study to be random and large. The bigger our sample size, the more accurate out findings will be towards our desired population. There is no golden number for how big a sample size should be, but anything typically larger than 100 is okay if the sample was random. Larger samples will yield more accurate results. Smaller samples can still offer us some insight, but not enough for it to be representative.

Regressions & an R Coefficient

A statistical staple in things like psychology and other areas of the social science field is the regression lines and the r coefficient. A regression line, also sometimes called a trend line, is a line that best fits the data and it’s typically linear. In this, X is the explanatory variable and Y is the dependant variable. Another way to think about it is by thinking that Y, the dependant variable, is the effect, and X, the independent variable, is the cause. So Y depends on X, and a change in X can cause a change in Y. Let’s look at an example by Levin (1997):

As we can see, an increase in height means an increase in calorie intake. So the correlation overall between height and calories in 0.8. In order to interpret what this coefficient number means, we can see what the statistician Jacob Cohen proposed:

| Small | 0.10 to 0.29 |

| Medium | 0.30 to 0.49 |

| Large | 0.50 to 1.0 |

So when looking at the correlation between height and calorie intake, we get a large correlation. Readers should remember that a correlation for Pearson’s R can be negative or positive, depending on the slope in the regression. An r of 1.0, for example, means that there is a perfect correlation between X and Y, but an r of -1.0 means a perfect negative correlation.

That r2, as seen under the graph, simply means how much of the dependent variable can be explained by the independent variable. To get r2, simply square Pearson’s r. In this case 0.8 x 0.8=0.64.

Correlation & Causation

No matter how many statistics classes you take, or how many internet arguments one gets in, it’s common to here that “correlation does not equal causation.” For example, the correlation between hours spent studying for a test and the grade you get on it may not be evidence of causation, especially since we can not prove that you studying led to you getting a certain grade. Although this is true, the effect size strength allows us to see if there is a casual association between the two variables we’re looking at. Although it does not show us causality, it may suggest an association between the variables we’re examining depending on it’s strength.

This brings us to what is known as a spurious correlation. A spurious correlation refers to a connection between two variables that appears causal but is not. For example, the correlation between premarital sex and negative health outcomes may appear causal at first, but controlling for confounding variables may show that there is no relation between the x and y variable after further controls are imposed. Those who have premarital sex may have more negative health outcomes, but is this due to premarital sex itself or other variables that have not been controlled for? It’s important to control for confounding variables when possible.

Effect Sizes & Statistical Significance

Effects sizes are simply ways of quantifying the difference between two groups. The greater the effect size, the greater the difference between whichever groups we are looking at, and the smaller the effect size, the smaller the difference between the groups we are analyzing. The most popular effect sizes, and the ones you really only need to understand when reading this, is Pearson’s r and Cohen’s d. There are other types of effect sizes, but I am tailoring this to fit what is required to understand this article.

Pearson’s r

As noted above, Pearson’s r coefficient tells us the strength between two variables. The correlation can only range between -1.0 and +1.0. Due to this, we can interpret Pearson’s r as an effect size. To determine the effect size for r, refer to the table given above.

Cohen’s d

Cohen’s d is the difference between two population means. It allows us to see the difference between the populations we’re looking at via their means. This is not a statistics class, so I won’t teach you how to calculate it. Instead, you can refer to this online calculator that does it for you (click here). To interpret how strong the effect size for Cohen’s d is, we can use this interpretation for effect size strength from Cohen (1992):

| Range | d effect size strength |

| 0 – .19 | Weak |

| .20 – .49 | Small |

| .50 – .79 | Medium |

| .8 or higher | Large |

Sometimes, researchers do not give us Cohen’s d, and thus we can’t see if the difference between two groups is small, medium or large. Luckily, if they supply a SD, mean value, and sample size, we can use the calculator up above to see it for ourselves.

Statistical Significance

Statistical significance helps us see if results are not due to chance alone. When something is “statistically significant”, that means our results were not due to chance–but if it’s not statistically significant then it was due to chance. For example, let’s say that the correlation between computer use and IQ is r= .5. If we were to run statistical hypothesis testing and found that the correlation is not statistically significant, then it means our correlation was due to chance.

Statistical significance is provided to us by something called a p-value. The p-value is the probability of how likely our result occurred by chance alone. If the p-value is small, it means the result was unlikely to have occurred by chance alone, and is thus statistically significant. A large p-value means the result is within chance or normal sampling error (i.e., the results occurred by chance). P-values range from 0 to 1, just like Pearson’s r. To interpret if a p-value is significant or not, we have to compare it to something called alpha (α). The two most common levels of α is α = 0.5 and α = .01. Alpha is decided by researchers beforehand.

If we use the two levels of α above, we can see when p-values are significant or not. If α = 0.5, for example, then p < α means the test is significant and p > α means the test is insignificant. The same rule applies to α = .01.

Unfortunately, many social scientists rely upon statistical significance to see if results are important or not. However, Cohen (1990) has stated that “I have learned and taught that the primary product of a research inquiry is one or more measures of effect size, not p values.” The American Psychological Association has noted that researchers should “Always provide some effect-size estimate when reporting a p value” (Wilkinson and Task Force on Statistical Inference 1999). The reason for this is because statistical significance alone does not tell us much, especially since an effect can be there even if hypothesis testing tells us that our results are not significant (see Wasserstein, Schirm, and Lazar 2019). I agree with Cohen, and thus will rely on effect sizes when they’re given or calculated instead of just seeing if the results are significant or not. This is why I gave a discussion on effect sizes, something I should’ve done in the last version of this response.

Now we’ve come to the section everyone wants, the response. This section will be formatted rather simply. Anything in bullet points will be what was said in the document, and what follows (i.e., what’s not in bullet points) is the response to the claim made and the studies used. Any claim that is similar to another claim will be included in the same little sub-sections, and sometimes some claims will be responded to in different sections and so I’ll tell you to go to that section for a response to that so there is no redundancy. Here’s an example of the format:

- Study Link

- Claim made

My response

Introduction Studies

- https://www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Black-Lives-Matter.pdf

- Extensive document on racial biases in our criminal justice system.

- Studies seem to indicate about 61-80% of black overrepresentation in prisons can be explained by higher black crime rates, with the unexplained portion largely attributable to racial bias.

- Remember – the factors which lead to disproportionate criminality amongst black Americans are also in large part a product of racial bias. Underfunded public programs, redlining, generational poverty, bad schooling, and myriad other factors which influence criminality can also be traced to racial bias.

The documents presented by The Sentencing Project attempt to compare arrests to % of prisoners in prison, or by looking at some measurement of crime and arrests rates. Since there is some unexplained variance, it’s attributed to racial bias without evidence. Let’s take at the first cited study in this document, Tonry and Melewski (2008). After comparing UCR data to prisoners by race %s, they found that a 38.9% disparity that could not be explained, replicating a previous study that used the same crime database as them. The 2nd study cited, Blumstein (1993), found a 20.5% disparity that was left unexplained with the same methodology as the first study. The 3rd study, Langan (1985), looked at NCS data, inmate surveys, and admission census. It was found that the amount of blacks in prison was higher than the number of black offenders reported in the NCS. In 1979 and and 1982, 84% and 85% of the variance could be explained by black crime, leaving the rest to possible racial bias. As the paper says, there may be other explanations as to what explains the remaining disparity which is not racism; as the footnote says,

Regional differences in the imposition of sanctions may account for these differences since blacks may be concentrated in regions of the country where prison sentences are relatively common among convicted offenders (blacks and whites alike). If that is the case, statistics for the nation could indicate that the probability of imprisonment is higher for blacks than whites even in the absence of racial discrimination in justice administration. Another explanation is that blacks may have on average slightly longer criminal records than whites, thereby increasing their chances of receiving a prison sentence. Other legitimate explanations of these percentages are discussed by Blumstein, supra note 2, at 1268-70.

As can be seen, the author does not fully endorse racism as an explanation and offers alternative hypothesis. Like the studies cited before this one and the others that follow, the authors do not test to see if racial bias can explain the remaining disparity. All they do is argue that racism could be an explanation, but offer no statistical tests to see if they’re correct. This will be explained later, but let’s continue. The final study cited is Blumstein (1993), but I have been unable to find an online version of this paper to see what data was used. Regardless, none of these cited studies can prove racism is to blame.

As was already noted up above, the researchers do not prove that the remaining disparity can be explained by racial bias. All they do is find that there is a disparity left, say it could be because of racism, and that’s it. No models are used to test this hypothesis, but readers gobble it up and say the remaining portion is “largely attributable to racial bias.” No statistical model is ran, no test is used to see if this is true, just an interpretation of the data by the author. It’s up to the authors to actually prove that this is the case, not to assume it is. Readers, especially those who watch Vaush, may find what I just said asinine, but it’s the truth. Either run a model to test your racism hypothesis and see if the results confirm your hypothesis, or do not make the claim. Unfortunately, what I said doesn’t matter since the researchers have a fancy degree and they’re authority figures, so degrees matter more than evidence.

To continue, though, studies looking at the NCVS and official crime databases yield essentially similar racial differences as do official statistics (La Free 1996, in Hawkins 1995; Wilbanks 1987). For example, after examining data over a 3-year period, O’Brien (2001, in Walsh and Ellis 2006) found that crime reports matched up with crime arrests for race, meaning that blacks were being arrested at the same rate that they committed crimes (see Wilson and Herrenstien 1985 for more). Harris (2009) found that the overrepresentation of non-whites in jail reflects their crime rates. A more recent study provided by the original Reddit comment noted that these studies still found an unexplained disparity, but as has already been noted above, they do not test to see if the remaining disparity can be explained by racism or not. John may tell Bill that 85% of the reason he got into NYU was because of his grades, but the remaining 15% could be due to his race. Bill is right to say that John can not prove this, and no amount of hypothetical arguments can prove this either without him testing his hypothesis. If the remaining disparity is due to racism, then it’s up to the supporters of this view to run a model to see if this is the case, the fact that none have done so is odd. Furthermore, it’s unknown if the data is only looking at inmates who went to jail for a certain year and then comparing it to the crime rates at that specific year; or if they’re looking at the total amount of people in jail and then comparing it to crime rates. If it’s the latter, then we should expect the data to be inflated since some people may be in jail for crimes not captured during that years crime statistics, especially if they have been there for years prior. Regardless, there is a remaining disparity, but this can not be pinned onto racism as the document asserts without actual evidence that this explains the remaining disparity.

Reasons for Black Crime

In the original edition of this response, the issue of why blacks commit more crime was not discussed. When working on this new response, I didn’t want to include it, but further thinking led me to discuss the issue on the reasons for black criminality. According to Vaush, the reason blacks commit more crime is due to “Underfunded public programs, redlining, generational poverty, bad schooling, and myriad other factors which influence criminality.” It’s unknown how some of these things lead to crime (e.g. how does redlining lead to blacks committing crimes?), but most likely there are interaction effects at play. For example, redlining may lead to blacks staying in poverty ridden locations, and the lack of resources leads to blacks committing crimes. Let’s discuss if this can explain black crime on closer inspection.

Generational Poverty

In the case of general poverty, the argument goes that historical sin has led to blacks being poor, and this lack of wealth was passed onto their offspring. Due to this, poverty is a reason as to why blacks commit more crimes. First, it’s important to discuss if poverty is leading to blacks committing crimes. In general, it’s agreed upon on that poor people commit more crimes. The question, though, is if poverty shares a casual relationship with crime. Although poor people do commit more crimes, this is not evidence of causality. Sariaslan et al. (2013) utilized a large sample of Swedish individuals born from 1975-1989. It was found that a 1 SD increase in neighborhood deprivation was associated with a 57% increase in the chances of being convicted of a violent crime. However, controlling for unobserved confounders made the association disappear.

After controlling for confounders, the association between neighborhood deprivation (poverty, basically) was shown not to be casual. So, once you control for familial confounding variables, the correlation between poverty and criminality is not casual as some have posited. So, although people in deprived areas may commit more crime, this is not because of deprivation. Similarly, Sariaslan et al. (2018) looked at a total of 526, 167 people in Sweden who were born between 1989-1993. Children of parents of the lowest income percentile were more likely to be convicted of a violent crime when compared to those born in a high income percentile.

Like the previous study, controlling for unobserved familial risk factors made the association go away–showing that there is no casual relationship between poverty and criminality, and the correlation between the two is spurious rather than casual. Furthermore, blacks and whites in similar economic conditions do not have the same level of crime. In a graph provided by Chetty et al. (2018), race differences in crime persisted even when comparing blacks and whites in the same income group. In fact, blacks in higher income ranks have similar crime rates as whites in lower income ranks (there was no difference when comparing white females and black females, but this isn’t an issue given that crime is primarily concentrated among men).

Zaw, Hamilton, and Darity (2016) found that rich black kids are more likely to go to jail than poor whites. A user on Reddit has responded to some claims I’ve made in this post, discussing the issue of richer blacks committing more crimes than poor whites. He claims:

The Zaw, Hamilton, and Darity study literally just doesn’t say what he claims it says. The study concluded that incarceration rates were higher at every level of income for blacks, not that rich blacks commit more crime than poor whites.

First of all, my claim on what Zaw et al. said is correct. I doubt he read the study since he also said, “If you want to do an actual debunk yourself, just look at the abstracts of the studies he cites.” Just read the study yourself, especially since abstracts can be misleading. Regardless, let’s look at this graph made from the data by Zaw et al.:

As can be seen, rich blacks are more likely to be incarcerated than poor whites. We can use incarceration rates as a proxy for crime since incarceration rates align with crime reports, as discussed in this article above. He also complains that some studies are uncited for the section talking about the economy and crime. Only one of them was uncited, which was Rubinstein (1992). A citation has been added to that source since I can’t find a version of it online.

And Wolfgang, Figlio, and Sellin (1972) remarked that in the 20th century, lower class blacks had higher levels of crime than lower class whites. Furthermore, the correlation between poverty and crime on a national scale is inconsistent: Ellis, Beaver, and Wright (2009) found that most studies show that crime rises when the economy actually improves: 17 found that crime rises when the economy improves, 10 found that crime rises when the economy is doing bad, 5 found no relationship between the two. Rubinstein (1992, “Don’t Blame Crime on Joblessness.” Wall Street Journal, Nov. 9) found that murder and robbery tend to increase when employment increase. In looking at predictors of violent behavior (which cause crime, duh!), poverty, the mother’s lack of education, and the mother’s unemployment were predictive for whites but not blacks (McLeod, Kruttschnitt, and Dornfeld 1994). Finally, race differences in crime persist even after controlling for socioeconomic status (Kornhauser 1978).

In conjunction with what was said above, percent black is a better predictor of crime than poverty when put into a regression. Kposowa, Breault, and Harrison (1995) analyzed crime variation across 2,078 U.S counties and found that the proportion of the county that was % black continued to predict crime even after controlling for county differences in poverty, divorce rates, income inequality, religiosity, population density, and age. This was true for both violent crime and property crime.

Templer and Rushton (2011) looked at crime across the 50 U.S. states and found that the percent of the population that was black was a stronger correlate than average income for murder rates (.84 v -.40), robbery rates (.77 v .06) and assault rates (.54 vs -.23) Income was a stronger correlate for rape rates than race, but the coefficients were weak. Rubenstein (2005) found a very strong correlation (r=0.81) between percent black and Hispanic of a state and the violent crime rate of the state. Conversely, the association between poverty and crime and unemployment and crime are 0.36 and 0.35, respectively. Other studies have also suggested this to be true (Beaver, Ellis, and Wright 2009):

All these lines of evidence cast doubt on poverty being role in black crime, especially when looking at the effect sizes.

Poverty may not cause crime, but why are blacks lagging behind whites in their wealth? Leftists often blame historical sin for this, arguing that discrimination and racism led to blacks not having access to things and thus they were unable to pass on their wealth, leading to generational poverty. As far as I know, there is no study that has shown that if blacks were not victims of historical sin, the black-white income gap would be small or nonexistent. Instead, it’s just story time with Leftists and them saying how “since this happened, it led to this and then this, and then that and a bunch of other things!” No piece of evidence is offered to show that if blacks weren’t discriminated against in the U.S., then they’d be at the same level or almost the same level as whites in respects to wealth. If anything, the null-hypothesis that racism is to blame for black poverty doesn’t hold up (see Last 2019). Some reasons blacks could be lagging behind whites in wealth and have a higher crime rate could be due to racial differences in behavior, something to be discussed below.

Redlining

In conjunction with generational poverty, redlining is argued to show how blacks were stuck in impoverished neighborhoods because they were denied loan. Due to this, blacks were stuck in impoverished locations which led to criminality and having lower wealth. As has already been noted above, the correlation between poverty and criminality is not causal, and controlling for income does not remove race differences in crime. In contrast to the standard left-wing argument, racial composition of a neighborhood does not correlate to the probability of someone getting a load once further variables are adjusted for.

Looking at data from Pittsburgh, Ahlbrant (1977) noted that race had no significant independent effect on loaning. Once socioeconomic status variations were controlled for, Dingemans (1979) found that ethnicity and age contribute little explanation on getting loans. Avery and Buyank (1981) that areas which where stably black and stably white did not differ significantly in loan rates once economic variables where held constant. Tootell (1996) looked at data from Boston and found that the racial composition of an area was unrelated to the proportion of loan applications that were rejected in the area. So, since race has nothing to do with loans once economic variables are controlled for, it’s doubtful that this can explain why blacks are in poverty.

Bad Schooling

When it comes to bad schooling, this is based on the assumption that blacks go to bad schools. This is dealt with in Last (2019). Does not need to be dealt with here.

Based on what Vaush has said in the past (e.g. this Youtube video), and even in the document I am responding to, it seems he takes race differences in crime to be due entirely due to the environment. Race differences, possibly, do not play a role — and if they do, then they’re environmental and not genetic. Since Vaush’s explanations for black crime do not explain the black-white crime gap, I will argue that race differences in social and psychological traits explain the disparity instead. These traits, once taken together, can possibly explain why blacks commit more crime, and why they lag behind whites in money. What follows next is a discussion on race differences in traits, and how they can explain the black-white crime/ wealth disparity.

Alternative Explanations for Black Crime

It has been shown that the inability or unwillingness to delay self-gratification affects many life outcomes. Using nationally representative samples, Moffit et al. (2012) looked at how well self-control measured in childhood predicted life outcomes at age 32 compared to IQ and parental socioeconomic status. Self-control was found to predict better health, more wealth, less criminality, and a lower chance of being a single parent. This held true even while IQ and parental socioeconomic status was held constant. Although, Moffit et al. found IQ to be a better predictor of wealth and adult socioeconomic status when self-control and parental socioeconomic status were held constant. Daley et al. (2015) looked at 16,780 British individuals and looked at how well IQ, childhood self-control, and class predicted adult unemployment. IQ and self-control both had a negative relationship with unemployment, and class failed to predict unemployment after IQ and self-control were controlled for.

Tangey, Baumeister, and Boone (2004) found that high self-control predicted a higher GPA, better social adjustment, less binge-eating and alcohol abuse, better relationships and interpersonal skills, secure attachment, and better emotional responses. This remained even after controlling for social desirability bias. Casey et al. (2011) looked at 60 individuals and remarked that those who showed lower self-control in preschool also showed lower self-control in their 20s and 30s. In a meta-analysis by Ridder et al. (2011), self-control was related to a variety of human behaviors like love, happiness, getting good grades, speeding, commitment in a relationship and lifetime delinquency. There was a small-medium relationship between self-control and outcomes, showing that self-control may not explain all of these variables fully, but it is a factor.

In a classic series of studies, Mischel (1958, 1961a, 1961b) found that black Trinidadian children given a choice between getting a smaller candy bar now or a larger one in a week tended, much more than matched white children, to choose the smaller, immediate candy bar. The difference between white and black children “so great as to make tests for the significance of the difference superfluous” (Mischel 1961a). Mischel reported undertaking the study because informants had suggested that “Negroes are impulsive, indulge themselves, settle for next to nothing if they can get it right away, do not work or wait for bigger things in the future.” Seagull (1966) looked at black and white 9 year olds who lived in New York City. Blacks and whites were offered the choice between being given a small candy bar now, or a larger one in a week’s time. Black children were more likely to ask for the smaller candy bar now than white children.

Herzberger and Dweck (1978) looked at a sample of 100 4th graders and asked them to rate prizes. After rating the prizes, the researcher showed the immediate prizes and and the delayed one. Per the study, “the choice pairs included: three nickels, two versus five nickels, two versus three nickels, a small candy bar versus a medium-sized candy bar, and a rubber ball versus an iron-on patch (the latter was inscribed with either ‘keep on truckin” or ‘try it—you’ll like it’).” Black children had lower self-control than white children even after controlling for socioeconomic status. Not all studies used candy, though.

In the mid 1990s, the U.S. government offered military personal two options for when they retired: A large lump sum of money now (immediate reward) or a yearly payment (delayed reward) which, overtime, will be more than the immediate lump sum of money. Warner and Pleeter (2001) looked at the data for 66,483 individuals and found that blacks were 15% more likely than non-blacks to take the immediate reward. Whites were .4% less likely than non-whites to take the immediate reward. Zytkoskee, Strickland, and Watson (1971) and Price-Williams and Ramirez (1974) featured Mexicans, whites and blacks. The choices varied slightly and consisted of the option of $10 now or $30 in a month’s time, a 5 cents candy bar now or a 25 cents candy bar in a month’s time. There was little difference between the Mexicans and blacks, both of whom preferred the immediate reward — white children preferred the delayed reward at a higher rate.

Castillo et al. (2011) had 82% of the student population of 4 middle schools in a poor Georgia school district. Subjects were asked if they want $49 now, or $49 + $x seven months from now. The x variable was positive and increased over time, so it would’ve been a lot of money. Black children had significantly lower control than white children. Andreoni et al. (2017) examined a total of 1,265 children who were asked if they wanted an immediate reward at the end of the day, or a larger reward the next day. The child’s race was significantly related to their level of patience and black children had lower levels of self-control than the white and Hispanic children. These differences weren’t explained by early assignment to school or parent preferences.

This attitude towards rewards can be described in a variety of ways: more rapid decay of reinforcement, unwillingness or inability to defer gratification, “extreme present-orientation” (Banfield 1974), impulsiveness, lower superego-dominance. In more crude terms, blacks are more impulsive than whites. Race differences in self-control matter since they could explain a variety of racial disparities. For example, Banfield argues that the primary cause of black poverty is because the lower class person lives from moment to moment– they are unable or unwilling to take account of the future or to control their impulses. Herrenstein and Wilson (1985) reported that poor blacks wanted to make a lot of money, but they left jobs if they were low paying while, ironically, saying that the work game is strong. W.J. Wilson also reported how blacks told ethnographers that their black unemployed friends were lazy; one person said that “many black males don’t want to work, and when I say don’t want to work, I say don’t want to work hard. They want a real easy job, making big bucks” (Wilson 1997). Lower self-control among blacks could partially explain why blacks are poorer than whites. Race differences in self-control can also help explain why blacks commit more crimes in the U.S. and all over the world (see Beaver, Ellis, and Wright 2009).

Race differences in self-control levels can also be moderately explained by genetics, especially since self-control is under some genetic influence. Beaver et al. (2008) found that the heritability of self-control lies at .56; Anokhin et al. (2011, 2015) found it to be at .30 at age 12, .51 at age 14, and .55 at ages 16 and 18; Isen et al. (2014) found it to be at .47. Recently, Willems et al. (2019) conducted a meta-analysis and found the heritability of self control to be .6. In conclusion, half of self-control can be explained by genes and races differ in self-control for genetic reasons and environmental reasons.

Given that self-control correlates with lifetime delinquency and income, two variables in which blacks and whites differ in, then this could be a factor that can help explain some of the reasons as to why blacks commit more crimes and have lower incomes. Adjusting for other variables does not close the gap, and still leaves it open — showing that environmental variables are not the reason as to why blacks have lower self-control. Along with self-control, or lack thereof, another mediating variable to help explain the black-white crime/ wealth gap is IQ.

As has been noted below and in other places, races do differ in mean intelligence. Whites, on average, have an IQ of 100 and blacks have an IQ of 85. This view is not heretic, and has in fact been supported in the overall scientific literature. Shuey (1966) in The Testing of Negro Intelligence reported on 382 studies involving 80 different tests administered on hundreds and thousands of black and white children, high school and college students, military personnel, civilian adults, deviates, and criminals. The average black IQ score in these studies were a bit below 85, and the average for whites was also a bit above 100. The average black-white difference was always close to 1 SD. Lynn (2011) reviewed hundreds of studies looking at race differences in IQ, and the black-white IQ gap was always 1 SD. Roth et al. (2001), which was a large meta-analysis which included more than 6,000,000 individuals, found that blacks score 1 SD lower than whites. Chuck (2013) looked at 100 years of testing done on black intelligence, and every study looked at found lower intelligence among blacks. Even The National Academy of Science reported that,

“Many studies have shown that members of some minority groups tend to score lower on a variety of commonly used ability tests than do members of the white majority in this country. The much publicized Coleman study provided comparisons of several racial and ethnic groups for a national sample of 3rd, 6th, 9th and 12th grade students on tests of verbal and nonverbal ability, reading comprehension, mathematics achievement, and general information. The largest difference in group averages usually existed between blacks and whites on all tests and at all grade levels. In terms of the distribution of scores for whites, the average score for blacks was roughly one standard deviation below the average for whites. Differences of approximately this magnitude were found for all given tests at 6th, 9th and 12th grades… The roughly one-standard deviation difference in average test scores between blacks and white students in this country found by Coleman et al. is typical of results of other studies” (Garner and Wigdor, 1982)

The American Psychological Association, which most people would agree is an authoritative source, even remarked how there is a gap between blacks and whites in intelligence (see Neisser et al. 1996). Since races differ in IQ, this could also help explain the high rates of black crime since IQ correlates with criminality.

Sources for the correlation between IQ and crime can be found here.

In 1914, the role of intelligence in crime was brought to attention by H.H. Goddard (1914) who found that the majority of people in prison were mentally deficient. After this point though, the relationship between intelligence and criminality was not only ignored, but unfairly rejected (see Hirschi and Hindelang, 1977). This was because of a paper by Edwin Sutherland (1931) titled “Mental Deficiency and Crime” where Sutherland argued that the cause of the association was because of poor testing conditions. He showed that as testing procedures became better, the correlation began to diminish itself. But, he wrongly assumed that over time, it would completely disappear.

Hirschi and Hindelang (1977) re-initiated the crime-IQ debate with a paper titled, “Intelligence and Delinquency: A Revisionist Review”. This paper fought against the sociological bias against the role of IQ in criminal behavior and adult delinquency and pulled from multiple studies available at the time to prove it is unjustified. Some of the most compelling data is explained in the following paragraph (all studies cited in the following paragraph can be found in Hirschi and Hindelang [1977]). First, they re-analyze data from Hirschi (1969) which had a sample of 3,600 boys from Contra Costa County, California. They find a gamma correlation of -0.31. Wolfgang et al. (1972) uses criminal data from 8,700 boys and splits them into groups by IQ. There was a clear association with a gamma correlation of -0.31 for whites and -0.16 for blacks. West (1973) uses data from over 400 boys from London. They find that one quarter of people with an IQ of 110 or higher had a police record whereas one half of people with an IQ of 90 or less had a police record. He concludes that IQ was a significant predictor of delinquency and that it survived as a predictor after controlling for variables such as family income and family culture. Toby and Toby (1961) showed “intellectual status” was a significant predictor of delinquency/non-delinquency, regardless of socioeconomic status. Finally, Hirschi and Hindelang report on data which shows that even self-reported criminal behavior correlates with criminality.

Spellacy (1977) looks at 40 violent and non-violent adolescent males and tests them on neuropsychological tests and on the MMPI scale. They tested the group on verbal IQ, performance IQ, and full-scale IQ (FSIQ). On FSIQ, there was a 12.4 point difference between violent and non-violent adolescents. The results were consistent across other tests of mental ability. Similar differences are analyzed by Holland, Beckett and Levi (1981) and Holland and Holt (1975).

Mears and Cochran (2013) used the NLSY data of white men and their AFQT scores and create an index of different forms of delinquency and how much the participants committed those forms of delinquency. They controlled for additional measures, like Cullen et al. in order to refine the correlation to AFQT scores as much as possible. But, instead of purely relying on regression analysis (as they explain it has issues for curvilinear data), they used GPS analysis. First, they provide the bivariate analysis results which show that lower IQ people to tend to commit more crimes, but once you are looking at people in the IQ range of 77-88, the propensity for crime drops off. Essentially, this implies an inverse U-shaped model. Then, when testing the relationship through GPS analysis, they do find an association where people in the 90’s IQ range commit the most crimes, but people below that and above that commit less crimes.

June Andrew (1982) uses digit span tests and verbal IQ scores for a young sample of delinquents. She finds substantial differences in both across non-violent delinquents and violent delinquents. Crocker and Hodgins (1997) follow a Swedish cohort of over 15,000 participants to age 30. The mentally retarded male participants were significantly more likely to have committed at least one violent offense, theft, traffic offense, or “other” offense. Similar results are found for women. A study by Oleson and Chappell (2012) actually looked at a sample of people of very high intelligence, or geniuses (mean IQ of the sample was 154.6). They found that even among geniuses, a statistically significant, negative correlation exists between IQ and use of violence, having killed another human (excluding warfare), and having kidnapped someone.

Diamond, Morris, and Barnes (2012) look at both individual IQ and prison-unit-level (different units of the prisons; groups) IQ and see if it relates to the amount of individual inmate violence. First of all, they find that the average IQ of prisoners is about 2/3rds of a standard deviation below that of the American population. This is line with other research that the IQ difference between criminals and non-criminals is about 8-10 points (Hirschi and Hindelang, 1977). Second of all, they find individual IQ negatively correlates with individual inmate violence and that differences in prison-unit-level IQ negatively predicts the amount of individual-level violence. This may be somewhat in line with the theory I presented earlier that group IQ differences matter more to variation in given outcomes than individual level IQ differences.

Lynam, Moffit, and Stouthamer-Loeber (1993) argue low IQ is a solid, causal predictor of delinquency. This is done through specific procedural measures such as using younger boys, so as to avoid the effect of prison lifestyle on intelligence, as well as controlling for test motivation. The latter procedure is done to combat the hypothesis that the delinquency-IQ correlation can be mediated by the fact that delinquents do not seek to do well in life and will not care about their results on a test. Additionally, multiple studies have shown that the IQ of delinquents was low before said individuals became delinquent (Denno, 1990; Moffit et al., 1981; West and Farrington, 1973). The present study used self reports to measure delinquency in the boys and controlled for social status, race, and test motivation to ensure the correlation remained regardless of these variables. A correlation of r=-0.22 is found for FSIQ and delinquency. Impulsivity mediated relatively little of the relationship; school achievement did not have any effect on the relationship for whites whereas it mediated the association for blacks.

Hodges and Plow (1990) and Ward and Tittle (1994) also control for both SES and race and find that low-IQ remains a significant predictor for delinquency. Wolfgang, Figlio, and Sellin (1972) compare one-time offenders and chronic offenders in intelligence. They control for SES and race and still find an 8.1 IQ point difference for whites and a 10.6 point difference for blacks. The latter difference is particularly interesting because most studies find a smaller association between IQ and crime for blacks (Hirschi and Hindelang, 1977; Lynam, Moffit, and Stouthamer-Loeber, 1993).

McDaniel (2006) used NAEP data to estimate the average IQ of different states. He finds a correlation of r=-0.58 for state IQ and violent crime rate. Bartels, Ryan, Urban, and Glass (2010) use state IQ estimates to create estimates on the relationship of IQ to criminal behavior. They sought to replicate and extend upon McDaniel (2006) by looking at various types of crimes at the state level. Bartels et al. find, like McDaniel, a correlation of r=-0.58 for state IQ and violent crime, despite the years tested being different. They extend with the following, significant correlations of -0.57 (murder), -0.29 (robbery), -0.41 (assault), -0.45 (property), -0.57 (burglary), and -0.29 (theft). McDaniel (2006) was also replicated by Pesta, McDaniel, and Bertsch (2010) who found states with lower average IQs had higher aggregate crime rates. They found a correlation of r=-0.76 between overall crime rate and state IQ estimates.

Templer and Rushton (2011) analyze data from the fifty United States on IQ and criminal behavior. IQ was correlated with murder at r=-0.64, robbery at r=-0.46, and assault at r=-0.47. Beaver and Wright (2011) look at over 200 counties and their IQ estimates. The correlation matrix can seen below in Table 1: primarily the violent crime rate was correlated with IQ at r=-0.58, the property crime rates was correlated at r=-0.40, the aggravated assault rate was correlated at r=-0.52, and the composite crime rate was correlated at r=-0.53.

Gendreau, Little, and Goggin conducted a meta analysis of 131 studies (1,141 correlations) on the relationship between specific factors and adult recidivism. “Intellectual functioning” had a mean correlation of r=0.07. This relationship was stronger than the SES-Crime relationship, but worse than most others. Kandel et al. (1988) finds that IQ is a protective factor against criminogenic, environmental differences and, in effect, reduces risk of criminality. Many others have agreed with the hypothesis that IQ indirectly affects criminality through causing criminogenic factors such as Herrnstein and Murray (1994), Magdol, Moffit, Caspi, and Silvia (1998), and Ward and Tittle (1994).

The 2009 edition of the Handbook of Crime Correlates finds a large number of studies on the correlation between IQ and criminality (Beaver, Ellis and Wright, 2009). They find that the supermajority find a statistically significant, negative association. Some fail to find a statistically significant association, and very few find a positive association. These results were the same for official offending, self-reported offending, and various forms of psychopathy related to criminal behavior. Additionally, the type of IQ matters; performance IQ has a stronger association than does verbal IQ, but both negatively predict criminality.

Ellis and Walsh (2003) review the international data on IQ and crime; of 68 studies on IQ and delinquency, 60 found statistically significant, negative relationships. The other eight only reported statistically insignificant relationships. Of 19 studies on adult offending and IQ, 15 found statistically significant, negative relationships. Of the 17 studies on self reported and IQ offending, 14 found a statistically significant, negative relationship. Of the (19) studies on the effect of IQ on antisocial personality disorder, all found a statistically significant, negative relationship. Additionally, the international meta analysis provided by the newer edition of the Handbook of Crime Correlates (Ellis, Farrington, and Hoskin, 2019) finds that far and wide, the majority of the studies show a statistically significant, negative relationship between official offending and IQ. Some studies were statistically insignificant and very few showed a positive relationship.

One criticism may be that low-IQ offenders are more likely to be caught, and thus the relationship between low IQ and criminality is an result of this issue. One study found that this was not the case, and that criminals that aren’t caught still have low IQs (Moffit and Silva 1988). Furthermore, controlling for SES still shows criminals to be low IQ (Jensen 1998).

Along with crime, IQ can also help explain some of the reasons as to why blacks earn less than whites and why blacks are in poverty. First of all, income is heritable, as found by twin studies. Hyytinen et al. (2013) looked at 19 previous samples in which the heritability of income was estimated. 42% of the income variation could be attributed to genes, while 9% was due to non-shared environments. It’s possible that blacks and whites could differ in genes associated with income, with whites having genes associated with higher income and blacks with genes associated with lower income. Regardless, Strenze (2007) looked at over 100,000 individuals and found that IQ correlates with income was at .22. This is important because IQ is a better predictor of someone’s socioeconomics in the future than their parents socioeconomics (Strenze 2007). Palmer (2018) also found that IQ was a better predictor of someone’s SES and poverty than their parental SES.

Since IQ is associated with income, it’s no surprise to see that controlling for IQ cuts the black-white difference in the probability of being in poverty and wages in half (Murray and Herrnstein 1997):

As can be seen, a large portion of the black-white differences in wages and being in poverty can be explained by IQ. The rest of the remaining disparity could be attributed to the race differences described above and below.

Another possible cause for black crime is race differences in MMPI scores. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, or MMPI, is a test that assesses an individual’s personality and psychopathology. In the book MMPI Patterns of American Minorities, it’s discussed how blacks score higher on psychopathy, schizophrenia, and on hyperactivity scales (Dahlstrom, Lachar, and Dahlstrom 1986). Gynther (1968) remarks how these findings are interpreted to show “estrangement and impulse-ridden fantasies … unusual thought patterns and aspiration-reality conflict,” and Dahlstrom, Lacher, and Dahlstrom note that the high score of blacks on hypomania indicate “outgoing, sociable, and overly energetic patterns; tendencies to act impulsively and with poor judgment.” Jones (1978) looked at 226 black and white junior college students and administered the MMPI and California Psychological inventory. Their results can be seen below:

As Jones remarks, “Blacks reported themselves as more dominant and poised socially, fundamentalist in their religious beliefs, concerned with impulse management, self-critical, psychologically tough, cynical and power oriented, conventional in moral attitudes, and conformist that Whites. Blacks also reported themselves as less adventuresome and likely to take risks, and less vulnerable and tender psychologically (an interaction effect suggests this is particularly true of Black males than whites).” White male scored higher on unconventional morality, meaning that their behavior is considered beyond conventional sexually and ethically, but this doesn’t align with reality given race differences in moral reasoning tests, something to be discussed below.

When it comes to women, black women scored higher on social dominance, compulsive-orderliness, self-criticism, psychological toughness, risk-taking, cynicism and power orientation, and conformity. Both black and white women tended to report themselves as more religious, and conventional in moral attitudes. These race differences held true even after holding socioeconomic status and years of education constant. Similar findings for women have been noted in another study.

Harrison and Kass (1967) looked at pregnant black and white females. It was reported that “Negroes reported themselves as more religious, intellectual, romantic, cynical, impulsive in fantasy, fearful, estranged, sociable, concerned with dreams, orderly, and somatically tense than whites and less masochistic, free of aberrant behavior, indulgent in minor crimes, self-conscious, and antagonistic toward school than whites.” A table for their findings show the differences found:

MacDonald and Gynther (1963) also found race differences in MMPI scales:

Race differences were smaller when looking at the high social class groups (1-2), but the differences in MMPI scale scores get more pronounced depending on the scale being measured and the social class. An issue with this is that blacks scored higher on L, which is the scale that checks if you’re lying when taking the MMPI test. Based on Cohen’s d, the differences are large (black-white male difference d=0.9; black-white female difference: d=0.7) and the smaller race gaps could be an artifact of blacks lying on the test. Regardless, the conclusion of racial differences in MMPI scores show that blacks are more cynical, have greater mistrust, conflict with authority, and “externalization of blame for one’s problems.”

After controlling for social status, IQ, and levels of education, the differences in MMPI scores go away. This does not mean that MMPI differences are a result of theses variables, rather that traits scores may also affect status and levels of education. For example, conflict with authority can stop advancements in social status and levels of education. Controlling for these variables may make the differences go away, but this does not mean the differences are simply artifacts. Some commentators have also made the claim that the MMPI test is biased against nonwhites, but the evidence does not support this (Prichard and Rosenblatt 1980).

Going back to morality, we should not assume blacks and whites are equal in their ability to morally reason. One way to measure someone’s ability in moral reasoning is to give them a test where the lead actor is confronted with a moral dilemma. The respondent is supposed to choose the proper action consistent with it. When it comes to these tests, delinquents preform poorly on them (Raine 1993). Not surprisingly, these tests have also found race differences. In a sample of 1,322 junior high school students, their mean score was 21.90 with a standard deviation of 8.5 (Rest 1979). In a study by Preston (1979, cited in Rest 1979), blacks got a mean score of 18.45, showing a weaker moral understanding with a Cohen’s d of 0.41. In a sample of 8,782 people, blacks were more likely to endorse statements such as “laws are made to be broken”, “there is no right or wrong ways to make money”, and “it is okay for a teenager to have fist fights.” The same has been found in blacks from Trinidad (d=-0.45 [Rest 1986]) and in Jamaica (d=-0.51 [Gielen et al. 1989, in Adler 1989]) when compared to whites. Since blacks score lower in tests that measure ones moral understanding, it’s no surprise that they are more likely to commit crimes.

- Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department

- Between 2012 and 2014, black people in Ferguson accounted for 85 percent of vehicle stops, 90 percent of citations and 93 percent of arrests, despite comprising 67 percent of the population.

- Blacks were more than twice as likely as whites to be searched after traffic stops even after controlling for related variables, though they proved to be 26 percent less likely to be in possession of illegal drugs or weapons.

- Between 2011 and 2013, blacks also received 95 percent of jaywalking tickets and 94 percent of tickets for “failure to comply.” The Justice Department also found that the racial discrepancy for speeding tickets increased dramatically when researchers looked at tickets based on only an officer’s word vs. tickets based on objective evidence, such as a radar.

- Black people facing similar low-level charges as white people were 68 percent less likely to see those charges dismissed in court. More than 90 percent of the arrest warrants stemming from failure to pay/failure to appear were issued for black people.

The issues in the Ferguson Report revolve around driving violations mostly, with the inclusion of small stuff like jaywalking, things like charge dissmals, and warrants. The issue of driving violations will be dealt with down below when talking about driving offenses, but the issue of charge dismissals is not racially biased. According to one study, “White males were no more likely than non-White males to have the charges dismissed” and “White females, in other words, were less likely than non-White females to have all charges dismissed” (Guevara, Herz, and Spohn 2006). So, to the degree there is a racial bias, it seems to favor blacks when looking at females but nobody of any race when looking at males.

Stops, Searches, and Arrests

- The Concentrated Racial Impact of Drug Imprisonment and the Characteristics of Punitive CountiesWhile White & Black Americans admit to using and selling illicit drugs at similar rates, Black Americans are VASTLY more likely to go to prison for a drug offense.

- In 2002, Black Americans were incarcerated for drug offenses at TEN TIMES the rate of White Americans.

- Today, Blacks are 3.7x as likely to be arrested for a marijuana offense as Whites, despite similar usage.

- 97% of “large-population counties” have racial biases in their drug offense incarceration.

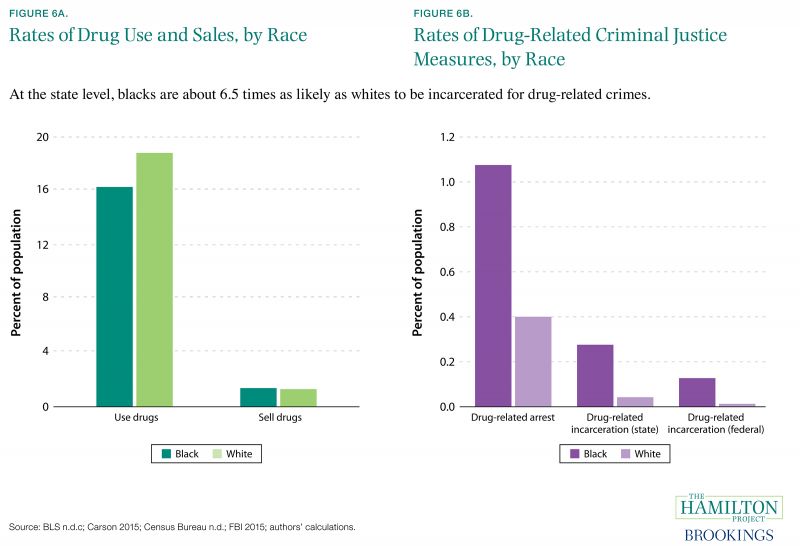

To know how these studies are done, all one has to know is that these studies get a large sample, and then ask the respondent if they have ever used drugs recently. From there, they usually compare drug use by race to arrest rates for drug offenses by race. So the first part (asking about drug use) is based on self-reported data. In credit to Vaush, it is true that studies have found that blacks and whites use drugs at similar rates, or that blacks have higher or slightly lower drug use than whites, but blacks are arrested more often for drug offenses. For example, Johnston et al. (2002) looked 43,700 students and gave them a questionnaire that asks about their drug use. According to Johnston et al., “Use also tends to be much higher among White students than among African American or Hispanic students.” Schanzenbach et al. (2016) reported that whites have a higher rate of drug use, as can be seen in the chart below, but black are arrested at higher rates.

Using data from SAMHSA, the ACLU reported that blacks report slightly higher cannabis use in the past month and past year, but whites report higher lifetime usage (50.7% for whites compared to 42.4% for blacks). Even though whites seem to use cannabis at higher rates overall, blacks are still arrested at higher rates for drug use (Edwards et al. 2020). Human Rights Watch (2009) remarked that blacks are more likely to be arrested for drug offenses, but this can not be pinned onto higher drug use among blacks since blacks and whites use drugs at similar rates (Gorvin 2008). Edwards et al. (2003) found similar results as the above 2020 revised report. Utilizing a probability-based sample of 4,580 college students who completed an online questionnaire, McCabe et al. (2007) found that Hispanic and white students reported higher drug use in college and before entering college when compared to blacks and Asians. The evidence seems quite clear, and to some only a fool would deny this as many analysis have found blacks to be more likely to be arrested for drug use even though nationwide data shows similar rates of drug use (see Owusu-Bempah and Luscombe 2020; Hughes 2020; SPLC 2018; see the report by the Justice Policy Institute).

Despite the overwhelming evidence showing this to be the case, these disparities are not a result of systemic racism. The null-hypothesis should not be that racism is to blame for these racial disparities, but rather it should be racial differences in how different racial groups use drugs and how often they do it. In reality, there is no reason to assume that the above findings are accurate for two strong reasons: [1] blacks are more likely to lie on self-report surveys, especially those that deal with crimes, and blacks are more likely to lie about their drug use when compared to whites, thus artificially decreasing their actual drug use rates; [2] racial differences in drug consumption can explain why blacks are more likely to be arrested for drug offenses, even if drug use by race is similar or lower for blacks.

Dealing with the first line of counter-evidence, criminologists have found that blacks are more likely to underreport their actual crime rates when asked. According to Cernkovich, Giordano, and Rudolph (2000: 143), there is “evidence that black males’ self-reports of delinquency are less valid than the reports of other groups: Black males underreport involvement at every level of delinquency, especially at the high end of the continuum.” Hindelang, Hirschi, and Weis (1981) report that self-reports are less valid for groups like blacks, with similar findings being remarked by Huizinga and Elliott (1986). Due to this, there is no reason to assume that blacks are being honest about their drug use. Although this is for crime in general, the same is true for drug use specifically. Page et al. (2009) did a urinalysis tests and asked the people in their study if they have used drugs recently.

After running a linear model, it was found that non-whites were more likely to say they have not used drugs recently when they in fact did. Falck et al. (1992) looked at 95 drug users and had them do a urine test after asking them if they had used drugs recently. In Table 3, they found that blacks were more likely to falsify their self-reports on opiate and cocaine use, as seen in the table below.

Feucht, Stephens, and Walker (1994) looked at 88 juvenile arrestees and had them do a hair test and urine analysis. In their urine analysis, blacks were more likely to lie about not using cocaine when they in fact did, as argued by Feucht and his colleagues when they said that “However, the higher rate of urinalysis cocaine-positive results for black arrestees suggests that the higher hair assay levels may actually indicate greater use of cocaine among the black arrestees in the sample.” Looking at marijuana, Fedrich and Johnson (2005) found a lower concordance rate within blacks, with the same being true for cocaine use.

Other studies have also found that blacks and non-whites are more likely to report lower drug use, even though testing them shows that they’re lying (see Miyong, Hill, and Martha 2003; Ledgerwood et al. 2008; Fendrich and Xu 1994). One study also found that blacks admit they they’d lie about drug use when asked, especially when compared to whites; 14% versus 6% for marijuana, and 19% versus 8% for heroin (Johnston, Bachman, and O’Malley 1984).

Furthermore, Ramchand, Pacula, and Iguchi (2006) noted that “African Americans are nearly twice as likely to buy outdoors (0.31 versus 0.14), three times more likely to buy from a stranger (0.30 versus 0.09), and significantly more likely to buy away from their homes (0.61 versus 0.48).” This shows that blacks are more reckless when buying drugs since it seems they’re more likely to buy it from someone they don’t know and use it outdoors where they can be caught, especially since these outdoor areas have higher crime rates where there is more police presence and blacks use drugs in areas with higher crime rates (Lagan 1995).

Some critics have pointed to this paragraph from Ramchand et al.:

“What these numbers show is that risky purchasing patterns among African Americans and their more frequent participation in transactions can account for only a relatively small amount of the observed differential in arrest rates. According to these calculations, Whites should still be arrested at a rate at least twice that of African Americans if the only thing driving these arrests were differential purchasing patterns. Instead, we observe in the real world that it is African Americans who are arrested at a rate that is twice that of Whites.”

This is supposed to show that differences in use and purchasing do not explain why blacks are arrested more often for cannabis consumption than whites. The issue is, it’s not supposed to. This line of evidence is supposed to be viewed with other lines of evidence, specifically lying about not using drugs. So, the reason blacks are arrested for drug use at higher rates is because they’re more reckless when buying and using drugs and they do them more often than whites. It just seems like they don’t do it more often because they lie on surveys. Not sure how this paragraph changes anything when you’re supposed to view it with other lines of evidence.

All these pieces of evidence, while viewed alone do not offer satisfactory explanations, do offer an alternative explanation when viewed together.

In conclusion, racism can not explain why blacks are more likely to be arrested for drug offenses. As has been noted above, these studies rely on self-reported data in which blacks are more likely to lie on than whites. The fact that drug testing shows opposite results from what places like the ACLU argue should cast strong doubt on the racism hypothesis. Racial differences in drug use and consumption also show that race differences in these areas can explain why blacks are more likely to go to jail for drug offenses than whites, even if drug use by race was similar or slightly higher for blacks. Purveyors of the racism hypothesis have yet to dispute these findings, instead relying on flawed methods of proving racism for racial differences in drug arrests.

- https://www.acludc.org/sites/default/files/2020_06_15_aclu_stops_report_final.pdf

- This ACLU report reviews 5 months’ of data from DC police stops & searches by race and outcome.

- The black population of DC is 25% greater than the white population, but black people were 410% more likely to be stopped by the police than white people

- This disparity increases to 1465% for stops which led to no warning, ticket or arrest and 3695% for searches which led to no warning, ticket or arrest.

- This data indicates the disproportionate stopping and searching of blacks in the Dc area extended massively beyond any disproportionate rate of criminality.

- The Problem of Infra-marginality in Outcome Tests for Discrimination

- Analysis of 4.5 million traffic stops in North Carolina shows blacks and latinos were more likely to be searched than whites (5.4 percent, 4.1 percent and 3.1 percent, respectively).

- Despite this, searches of white motorists were the most likely to reveal contraband (32% of whites, 29% of blacks, 19% of latinos).

- https://drivingwhileblacknashville.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/driving-while-black-gideons-army.pdf

- Between 2011 and 2015, black drivers in Nashville’s Davidson County were pulled over at a rate of 1,122 stops per 1,000 drivers — so on average, more than once per black driver.

- Black drivers were also searched at twice the rate of white drivers, though — as in other jurisdictions — searches of white drivers were more likely to turn up contraband.

- A large-scale analysis of racial disparities in police stops across the United States

- Enormous study of nearly 100,000,000 traffic stops conducted across America.

- Analysis finds the bar for searching black and hispanic drivers’ cars is significantly lower than the bar for white drivers.

- Additionally, black drivers are less likely to be pulled over after sunset, when “a ‘veil of darkness’ masks ones’ race”.

Before we continue, Vaush is correct to argue that blacks are stopped and searched more often than whites. This finding has been replicated in many locations across America, but there are few problems with this. To determine if racial bias may be present, researchers use a benchmark based on population demographics. For this benchmark, researchers compare the racial distribution for x to their groups total population. For example, say that in California 45% of people arrested for drugs are black but blacks are only 12% of the total California population. Since the racial distribution for drug arrests among blacks is higher than their total population, then this is evidence of racial bias since the two distributions do not align. Readers with an IQ of 90 can see how wrong this. First of all, we should not expect racial distributions to align for most stuff; second of all, blaming this disparity on racism doesn’t work unless it can be explained by racism with evidence — not just with the existence of a disparity. The null-hypothesis should not be that racism is the cause of the disparity, because if this is so then any racial gap is a product of sin rather than of differences.

Let’s take another example that relates to the topic at hand. Say that on the 105 freeway in Los Angeles 54% of drivers pulled over and searched are black, but blacks are only 23% of the Los Angeles population. Using the benchmark method used by many social scientists, they find that racism is responsible for this disparity since the two racial distributions (% black drivers stopped and their population % in L.A.) do not align and thus they must reflect racial bias. Instead of the social scientists seeing if racial differences in driving behavior can explain this disparity, they just argue that it’s because of racism because of their benchmark used. Because of this issue with this benchmark, it’s not exactly a good benchmark (see Ridgeway and MacDonald 2010 for more). Another benchmark used is the hit rate benchmark.

According to this benchmark, blacks being stopped and searched more is not a result of racial bias if their stop rates reflect their successful hit rates. If their stop rates and hit rates do not align — or rather their stop rate is higher than their hit race — then racial bias does seem to play a role. To repeat what I’ll say in the next following sections, hit rates do not matter. Say you’re a campus officer and there are people who wear blue backpacks and black backpacks. While patrolling the campus, you notice that those who wear black backpacks are more likely to commit campus violations/ show suspicious behavior. Due to this, you stop them more often and search them — but it turns out that those who wear blue backpacks are more likely to have contraband. Simply knowing their backpack color doesn’t help you see who to stop and search, but behavior and violations do. The final sentence will make sense in the following sections, but this will be repeated again near the end.

Overall, the evidence does suggest that non-white drivers are more likely to be stopped than white drivers. This is not an area of dispute, but the reasons for this disparity are. Regardless, let’s continue onto what the evidence for traffic stops by race tell us. Explanations for this disparity won’t be given in this section since this is more of a literature review, but it will be given in the next section.

Reviewing 5 months of data, the ACLU (2020) looked at D.C. police stops and searches by race. Black people made up 46.5% of the D.C. population but made up 72.0% of stops overall, 86.1% of stops that led to no warning or ticket, and 91.1% of searches that led to no warning or ticket. Although the ACLU does say that they really can’t say that this disparity is because of racism, they do say that it can be because of racism because (1) most black stops are unjustified; (2) blacks are more likely to be stopped in white areas and; (3) blacks are more likely to be searched than whites despite whites being found with contraband more.

Using a population benchmark, a California study by Durali et al. (2020) found that despite being 6.3% of the population according to ACS data, 13.4% of blacks were stopped by police. According to their findings, “a higher percentage of Black individuals were stopped for reasonable suspicion than any other racial identity group”:

Furthermore, blacks were searched more often despite whites yielding contraband at a higher rate than blacks. Blacks were also more likely to be stopped and arrested in the morning than at night, something called the “veil of darkness (VOD)” — when one’s race is masked at night. According to the VOD logic, this supports the hypothesis of racial bias since black drivers are less likely to be stopped at night when one’s race is harder to make out.

Looking at the San Diego Police Department (SDPD), Berjarano (2001) remarked that blacks only make up 8% of the San Diego population but 12% of all those stopped, and 14% of those stopped for equipment violations. Similarly, Zingraff et al. (2008) found that although blacks make up only 19.6% of licensed drivers in North Carolina, 22.9% of traffic tickets were issued to blacks. In Florida, blacks made up 22% of all seat belt citations but only 13.5% of the Florida’s drivers (ACLU 2016). These citation differences could not be explained by seat belt compliance since the difference in seat belt compliance between blacks and whites was not large enough to begin with (91.5% v. 85.8%). Similar results have been found in Maryland and Illinois (Harris 1999; ACLU 2014), with whites being more likely to be found with contraband in Maryland. One of the more popular studies comes from Lamberth (2010) in New Jersey. Despite blacks making up only 13.5% of drivers on the road, they made up 42% of those stopped by police.

In a more recent study looking at over 100 million traffic stops across America, Pierson et al. (2020) found that blacks and Hispanics were more likely to be stopped at higher rates than whites, more likely to be searched despite whites having more contraband, and blacks are less likely to be stopped at night than in the morning. This study, though, did not use a population benchmark and instead used the threshold test (Simoiu, Corbett-Davies, and Goel 2017). This test uses the rate at which searches occur and their success rate (i.e. they find contraband), with them finding that the bar to search non-whites is lower.

Looking at national data, Persico and Todd (2006) looked at 15 studies and looked at their hit rates, with Last (2019) making their table clearer and adding a difference(s) section:

As can be seen, there are regional differences in hit rates by race. Overall, whites have a higher hit rate (i.e. being found to have more contraband) than blacks, with the difference being 2.4).

Based on all this evidence, some would conclude that this disparity is due to racial bias in the criminal justice system. Indeed, this has been the position taken in some of the studies cited above, and in the media with them calling blacks being stopped and searched more than whites “driving while black” (e.g. LaFraniere and Lehren 2015; Brown 2019; Lartey 2018; Gold 2016). Good research does not just leave it here, it attempts to explain the findings instead of blaming it on a ghost (racism). Although blacks are more likely to be stopped and searched than white drivers, the racism hypothesis could be argued with racial differences in driving behavior.

Looking at the National Survey of the Use of Booster seats, we find racial differences in seat belt usage (Pickreall and Jianqiang 2009). These differences are larger between the ages of 13-15, and smaller in older age groups. Although we have these differences, they are not large enough to explain racial differences in driving stops — except at a younger age.

If non-whites live in areas where police aggressively enforce seat belt violations, then blacks will be more likely to be stopped.

While there seems to be very little data looking at racial differences in driving violations, the best evidence comes from criminologist Heather MacDonald. In the context of New Jersey and North Carolina, MacDonald (2016) notes: